Celebration and challenge

Posted on 03 September, 2020

https://poutamapounamu.org.nz/news/2020/celebration-and-challenge

Insights into the vision of Te Hurihanganui

Lee Rangitaawa, Seiin Paul, Minister Davis, Kyia Butcher, Cassiopeia Harrison, Minister Martin

On the 10th of June Te Hurihanganui was launched in Porirua by Minister Davis and Minister Martin. It was a milestone for those who have worked to bring this about, especially for the Mātanga group who brought their experience to the Ministry of Education to inform this government commitment.

On the 10th of June Te Hurihanganui was launched in Porirua by Minister Davis and Minister Martin. It was a milestone for those who have worked to bring this about, especially for the Mātanga group who brought their experience to the Ministry of Education to inform this government commitment.

The mood at the launch, as can be seen in these images, was very much one of celebration and anticipation.

One of those present was Children's Commissioner, Judge Andrew Becroft. Last year's report Education Matters to me undertaken by The Office of the Children's Commissioner and the New Zealand Schools' Trustees Association was one of many that the Mātanga fed into their deliberations to consider not only the issues, but where is the evidence, the practices and the pedagogy that have proven to work best for Māori?

One of those present was Children's Commissioner, Judge Andrew Becroft. Last year's report Education Matters to me undertaken by The Office of the Children's Commissioner and the New Zealand Schools' Trustees Association was one of many that the Mātanga fed into their deliberations to consider not only the issues, but where is the evidence, the practices and the pedagogy that have proven to work best for Māori?

The day of the launch has passed and for the Mātanga it is now a time of reflection as they wait to see what steps the Ministry take to operationalise their input.

The day of the launch has passed and for the Mātanga it is now a time of reflection as they wait to see what steps the Ministry take to operationalise their input.

In the following article they provide insights into their thinking and are explicit about the challenge that has been laid down, for them and for all educators in Aotearoa, New Zealand.

Te Hurihanganui: Listening to the experiences of the Mātanga

Abstract

In this article we share the work undertaken by the group of Mātanga (experts in their particular field) who were invited to develop a Blueprint in response to the incoming coalition Government’s call to restart Te Kotahitanga. This Blueprint and the potential system work that will emerge, have been named Te Hurihanganui.

In this paper we outline the context for developing this work and the main events leading up to its launch. These events are viewed from the perspectives of the Mātanga.

Introduction

In 2018, a one million dollar budget allocation enabled the Ministry of Education to consider what a new version of Te Kotahitanga (translated as ‘unity of purpose’) might look like. Te Kotahitanga, a successful secondary school reform programme (Bishop, Berryman & Wearmouth, 2014), had been terminated by its funder, the Ministry of Education, in 2013 at one of the high points of its success (Alton-Lee, 2015). This new budget work had to fit within the key priorities of the Ministry of Education’s Work Programme, and to progress the coalition Government’s agreement to restart Te Kotahitanga. The work also needed to align with the Government’s cross-agency Child Wellbeing Strategy.

To do this work, a group of ten Mātanga were invited to come together to co-design a Blueprint for a new approach alongside two members of the Ministry of Education’s Policy and Professional Learning teams.

The Mātanga group comprised well-known and well-respected leaders in transformative change for Māori within the New Zealand system. This co-design team needed to conceptualise an approach that would work in English medium education settings, together with any interconnected Māori medium settings, and be able to work from early childhood to senior secondary school. In these settings the approach needed to be able to address bias, strengthen equity and accelerate educational achievement and wellbeing of Māori learners.

This article presents Mātanga reflections of what they did and how they believed this work could be used for the potential betterment of future generations of learners. It concludes by reminding us of the enduring threats of appropriation, misinterpretation and potential ongoing marginalisation of Māori learners if this work is not undertaken with urgency and in ways that align culturally within an “ethical space of engagement” (see for example Nehiyew scholar, Willie Ermine, 2007).

Background - Why the need for reform

Over successive generations in New Zealand, our state education system has socialised a dominant narrative, reinforcing privilege based on the English language and colonial values (Bishop & Glynn, 1999). As in many colonised countries, education for Māori has largely been undertaken against an impositional and deficit background of imposed colonial belief systems, misunderstandings, bias and racism (Shields, Bishop & Mazawi, 2005). This, together with the devaluing and suppression of te reo Māori and values, has perpetuated ongoing disadvantage through colonisation for disproportionate numbers of Indigenous peoples worldwide (Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o, 1986).

In New Zealand, the cumulative impact of this is seen across the education system in the devaluing and rejecting of te ao Māori (a Māori worldview), te reo Māori (Māori language and an official language of New Zealand) and mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) in many parts of the system. The exception is where Māori have achieved greater autonomy and self determination in setting the schooling agenda (Kaupapa Māori settings). It is also seen in the bias, prejudice and racism concerning Māori and the inequitable outcomes across all important social indices including education (New Zealand Schools’ Trustees Association (NZSTA) & Office of the Children’s Commissioner, 2018; Office of the Auditor General, 2012). Disrupting the inequity, racism and bias perpetrated on Indigenous peoples will require Indigenous leadership and knowledge as well as other significant transformative actions, if, as a system, we are ever to support and sustain Māori success in education (Alton-Lee, 2015; Berryman & Macfarlane, 2017).

Those who accepted the invitation to join the Mātanga group were Jim Peters, Professor Wally Penetito, Mere Berryman as the chair, Daniel Murfitt, Professor Roberta Hunter, Te Waipounamu Teinakore, Dr. Lesley Rameka, Hurae White, Therese Ford and Whetu Cormick.

Their collective experience and evidence about what would work for Māori students ensured that this group could build on the lessons learnt from Te Kotahitanga and subsequent programmes, while also considering the current political context and policy system settings.

Reflecting on this opportunity

Reflecting on the opportunity to be Mātanga, Roberta Hunter, better known as Bobbie, a woman of Manahiki and Aitutaki, recalled that:

Being a member of this Mātanga group was a humbling experience especially given that the goal of the group was to address the most critical challenge currently facing Aotearoa-New Zealand.

Whetu Cormick from Ngāti Raukawa ki Wharepuhunga and the current president of the New Zealand Principals’ Federation also spoke of the privilege of being invited onto such a group:

I was proud to have been selected to participate in the development of Te Hurihanganui - a Blueprint for transformative system shift.

Wally Penetito from Ngāti Haua, Ngāi Raukawa and Ngāti Tamaterā, reflected that the Mātanga group was unique in its breadth and experience, suggesting that:

Our chair, Professor Mere Berryman has drawn together a very diverse group from a range of disciplines and experiences who share several powerful points of view.

He understood that for a number of reasons, getting greater equity from the education system for Māori, would not be easy or straight forward:

The education system has difficulty delivering on its promise of a fair go in schooling for all New Zealanders. There is an urgent need to better equip teachers, administrators and bureaucrats with the tools to identify and counteract the numerous biases that corrupt our education system. Institutional racism plagues the system and is so embedded that it often is taken-for-granted as portraying ‘that’s the way things are’.

Te Waipounamu Teinakore from Waikato Tainui and Ngāti Haua, explains the fundamental challenge and urgency in mapping out a system change when cultural and systemic change is necessary:

When a system validates the beliefs and philosophical ideologies of the dominant culture they themselves struggle to see the injustices on which it was built. Yet those who continue to be underserved and disabled by this system insist that “Enough is enough” and there has to be a better way. We all knew that something had to change but more importantly to do nothing would see us sitting at the same table in 50 years discussing the same issues.

Daniel Murfitt, principal of William Colenso College and principal in Phase 5 of Te Kotahitanga, understood the opportunity and potential solutions that they were presented with. He also understood that while there were proven approaches to draw from, the system itself would also need to be transformed:

We came together with the sole aim of changing the status quo for Māori within the education system of Aotearoa. We were given the licence to bring our experience to the table and come up with a blueprint of what we know works, what the evidence tells us works, what we have seen others do that works, and what we believe needs to be done to spread this mahi across and within the system.

Although Mātanga knew that sites of excellence could be found in some English medium schools they agreed that exemplars in which Māori students were enjoying and achieving educational success as Māori were more likely to be found in kaupapa Māori settings. Within these largely decolonised settings, Māori culture, identity and language are actively prioritised and celebrated and whānau Māori (Māori families) are more likely to be an active and valued part of their children’s everyday learning and cultural experiences.

Dr Lesley Rameka of Ngāti Raukawa and Ngāti Tukorehe descent, who brought expertise from her work in the Early Childhood sector also saw the reframing of the learning contexts as critical to the change required:

We require the reclamation of Māori ways of knowing and being through affirming the validity and legitimacy of Māori language, culture, identity and knowledge within educational contexts. This we believe will establish the foundation for Māori success across all sectors of the education system and will support Māori cultural, social and economic wellbeing.

The Mātanga understood that supporting Māori learners to experience education success in English medium settings, first required an understanding of and response to the pervasive historical colonial context and its continued dominance over English medium schooling. Just as Kaupapa Māori had claimed the space in which to decolonise and be self-determining, changing the more than 90% of English-medium settings would require significant and coherent action and commitment.

Therese Ford from Ngāi Takoto is actively working with school leaders to take up this challenge:

Fundamentally we have an opportunity to decolonise and subsequently transform our education system and wider society.

Hurae White of Ngāti Mahuta, Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Pikiao and Ngāti Ruahikihiki descent agrees this will require a focused and determined approach:

We have unapologetically highlighted the need for educators to expose bias.

It challenges all educators to be brave, bold and brilliant to get the huge shift that is needed to make a real difference for our tamariki. I believe this mahi is pivotal and supports our tamariki to be proud of their whakapapa and have their heritage acknowledged as a strength as tangata whenua.

Therese Ford has seen the impacts and opportunities of re-orientating educational settings:

De-centring entrenched beliefs and practices can open up the opportunity to critically consider alternative decolonising responses, particularly for children and whānau who are currently the least well served in our system.

Such responses would include recognising the mana of whānau and genuinely valuing the expertise they have and the aspirations they have for their children. Recognition of mana, expertise and aspirations however, will not go far enough.

Determined acts of collaboration that enable whānau to fully contribute so that educators at all levels of the system can learn from and with their Māori communities would increase the potential for transformation.

Moving forward, the Mātanga understand that the unfulfilled promise of the Ka Hikitia Māori strategy (Ministry of Education 2008; 2013) would be essential for the system shift that is needed (Office of the Auditor General, 2013).

This strategy was a deliberate call to educators across the New Zealand system to step up their efforts to ensure more Māori students were enjoying and achieving educational success as Māori. Despite the best intentions of the policy makers and the desire of principals and teachers to see the best for their Māori students, the introduction of the policy alone was not sufficient to disrupt the ongoing patterns of power, resistance and pedagogy that perpetuate Māori student underachievement (Berryman et al., 2016). To ensure all learners and their whānau feel they can belong within the systems and environments that we as educators create, a strong and clear strategy such as Ka Hikitia, properly supported, will be required for successful transformation of the system. Rather than continue to pathologise whānau Māori or abrogate responsibility to change, a system step up must be undertaken with whānau rather than continue to be done to whānau.

Hurae White explains:

Culture is positively powerful when ākonga feel safe and secure to bring their perspectives and experiences to their learning environments. For far too long Māori children have been expected to leave their Māoritanga at the school gate, assimilate and ultimately become ‘Pākehā’ in order to survive the education system here in Aotearoa.

Asking the critical question

The Mātanga accepted the invitation to contribute to this political initiative after deep consideration. We knew that government task forces such as this are a regular occurrence, and our collective histories would forewarn that top down political initiatives such as these have not always served Māori, our own people well, however, we received assurances from the Ministry of Education that this would be a process of true co-design. As a group of Māori, a Manahiki, Aitutaki and a Pākehā academic/educator, decolonising the system was something we all believed in and wanted to contribute to. Furthermore, our meeting and coming together was also seen as an important opportunity for collaboration across the sector.

Jim Peters, a descendant from Ngāti Wai, Ngāti Hine, Ngā Puhi and Clan McInnes suggested that:

The group were aware of the need for best practices and positive perspectives at all times. Their collective viewpoints must be of great help in the development of the next phase, inclusive of pre-school, primary and secondary school content and teaching practices. The Mātanga group brought to their work a comprehensive understanding of the educational landscape for Māori in Aotearoa, as well as an understanding of the complexities of the education system.

Daniel Murfitt spoke of the makeup of the Mātanga group:

It was important that the group included representation from people actively working with Māori students and whānau within all sectors of the system. [If it was to be a true co-design] it was also important that Ministry of Education people were involved as well.

What the Mātanga did

To help us consider a range of related perspectives, Dr Adrienne Alton-Lee was invited to bring perspectives from the Best Evidence Synthesis with particular regard to what had worked and what hadn’t worked for Māori. (Click to view Dr Adrienne Alton Lee’s presentation)

Mātanga were then asked to bring and present, what they believed had worked for Māori from their own particular settings. Their experiences were presented at a two day wānanga held on Huria Marae in Tauranga, at which other groups including students and iwi were also invited to present. From this experience the main themes were discussed and began to be prioritised for the Blueprint. To contribute to their discussions and decisions, Mātanga were able to visit any of the sights that they had heard about, and two, at their own cost, went to hear Robin DeAngelo (2011) in Melbourne talking about bias, prejudice and racism as underpinning principles in other systems across the world.

A new name was also needed to reflect the transformative nature required of the work and locate this initiative within the wider Education Work programme. After lengthy discussions, Kingi Kiriona with tribal affiliations to Ngāti Ruanui, Ngāti Kahungunu and Ngāti Apa, gifted the name Te Hurihanganui, providing the following explanation:

… it is said that Ranginui (the Sky Father) and Papatūānuku (the Earth Mother) were separated by their son Tāne Mahuta and his brothers. Such was the grief of both parents following their separation, and as an act of aroha, the children elected to turn their mother face down to avoid one parent seeing the sadness and despair of the other. This act became known as ‘Te Hurihanganui’, the great change or turning point, from which mankind evolved into Te Ao Mārama (the World of Light).

We agreed that Te Hurihanganui and this story were symbolic of the significant action required to achieve transformative education system reform. We recognised that to realise the educational potential of ākonga Māori, this new initiative must be revolutionary and act as a turning point for the system. However, in accepting the name, Te Hurihanganui, responsibility must also be taken for the courageous guardianship that this name and initiatives associated with it, would require.

Te Waipounamu Teinakore explains:

The name itself calls for disruption of the status quo a turning point seeking enlightenment for all. Te Hurihanganui provides a platform for us to do things differently, to focus on the things that make a difference and have the courage to stop doing the things that don’t.

It’s going to take a collective approach, and we all have a vital role to play. The decisions that we make today will shape the decisions that our children have to make tomorrow.

The following whakatauākī from Kingi Tawhiao reinforces Te Waipounamu’s thinking about the need to do this important work interdependent of each other’s contribution if we are to succeed. If anyone of us tries to do it on our own, they and the kaupapa, are likely to be exposed and vulnerable.

Ki te kotahi te kākaho ka whati, ki te kāpuia e kore e whati.

When reeds stand alone they are vulnerable, but together they are unbreakable.

The design principles

Based on our collective experiences and evidence of what works for Māori in education, the following six design principles were identified as a central part of the Blueprint. We believe all principles, working interdependently and in synergy, are critical for transformative education system reform.

- Te Ao Māori – Rich and legitimate knowledge is located within a Māori worldview. Under Te Tiriti o Waitangi, the education system must create and hold safe spaces for this knowledge to reside, supporting Māori to live and succeed as Māori.

- Tino Rangatiratanga – Māori exercise authority and agency over their mātauranga, tikanga, and taonga. In order to access this knowledge, Māori leadership is essential. Through decolonisation of the education system, Māori potential will be realised.

- Whanaungatanga – Whānau relationships are an exemplar for authentic, meaningful and transformative relationships in education. These relationships are based on mutual trust and respect from which shared understandings and reciprocal benefits can arise.

- Te Ira Tangata – Everyone is born of greatness and imbued with inner potential and conscious awareness. This brings with it the responsibility to be critically aware of ourselves, our world, and each other.

- Mana Ōrite – Te Tiriti o Waitangi is the foundation for equal, reciprocal, respectful and interdependent relationships between Māori and non-Māori (Pākehā - of colonial heritage, and tauiwi - more recent migrant of refugee).

- Te Hāngaitanga – We must take collective responsibility for ensuring Māori can enjoy and achieve education success as Māori. This can be achieved if all within the education system (Māori, Pākehā and Tauiwi) work in unison to understand and address these design principles.

Lesley Rameka highlighted the importance of exposing and disrupting how a particular set of power dynamics have continued to maintain the current inequality in our system:

Te Hurihanganui marks a turning point in our education system. It provides a blueprint for a consistent and coherent programme of system change, in early childhood education through all levels of schooling and tertiary education.

At its core is the need to expose underlying assumptions that obscure power dynamics in the ‘common sense’ beliefs, educational theory and practices that maintain power structures and inequalities.

Bobbie Hunter spoke of how the Mātanga undertook an investigation into what was perpetuating the inequalities in our system, despite repeated policies designed to eradicate it:

Te Hurihanganui is a courageous document and reflects what is possible when a diverse group of people, artfully led by Professor Berryman who allowed a safe space for wide ranging views to be expressed, are able to critically consider key issues not often ‘outed’.

Fundamental recognition was given to the ever-lingering effects of colonisation embodied in an education system which continues to support institutionalised racism and structural inequities both in the schooling systems and in the wider bodies which oversee the schooling systems.

The Blueprint with the design principles above were used to propose a budget bid that was submitted by the Ministry of Education to Ministers Davis and Martin. The proposal received a budget allocation of $42 million to be used over the next three years. Te Hurihanganui was launched at Porirua on June the 10th this year in front of government and Ministry officials, the Commissioner for Children, the Mātanga and Māori students, whānau, iwi and Maori Television. The presence of those from schooling and Early Childhood, who the Mātanga believed were the targets for system reform, were noted as being very limited.

Important considerations

The sharing of individual experiences by the Mātanga and their engaging with each other in the co-design process resulted in detailed consideration of the realities of implementing a system change such as was proposed.

Mātanga investigating sites of effective practices reported committed leadership, articulating their moral purpose and driving ongoing cycles of learning and unlearning.

Moving beyond the rhetoric to activate their own agency, these leaders grew their appreciation of what is possible.

Whetu Cormick describes spreading these understandings through:

A blueprint and processes to decolonise our racist education system will help us understand how teaching and learning are culturally situated activities; that parents and whānau are partners in their children’s education; and how important it is to include resources that reflect te ao Māori perspectives.

Lesley Rameka noted the holistic and interdependent nature of learning and wellbeing requires comprehensive action:

As Mātanga, our goal is that Te Hurihanganui will move the focus beyond ‘dabbling’ around the edges of issues, to dealing with deeply embedded structural inequalities and positionings.

All the Mātanga speak of the commitment required, and as Bobbie Hunter says:

There is a need to call out, name, and then address the many factors which have caused a failed education system for many Māori students. Unless the many factors are addressed then equitable outcomes for all learners will remain an illusion.

Te Hurihanganui has the potential to be transformative and liberating but that will require enormous courage and an open transparency on the part of all participants going forward.

Daniel Murfitt reflected on how wholehearted engagement with the kaupapa inevitably strengthens relationships, grows knowledge and the collective resolve for change:

As members of this group we came together as strangers and ended up being a whānau. The mahi involved eight months of wānanga and research, but also involved decades of work and experience that every Mātanga brought to the table. This experience and mahi could not be replicated by doing what has always been done nor will the outcomes be secured without deploying that evidence and experience together in implementation.

These important considerations have informed a number of deliberate and staged pathways forward that the Mātanga believe would achieve the aspirations of Te Hurihanganui.

A position for a director within the Ministry of Education was advertised and we understand that over the next three years, a group of Kaitiaki or guardians will be invited to co-govern Te Hurihanganui with members of the Ministry leadership team. No doubt following the usual processes of procurement, a Request for Proposal will be let, interested parties will propose their intentions and potentially new groups will be chosen to participate with the Blueprint.

Although the Mātanga have one more invited meeting with the Ministry of Education, we have been told, our role has finished. This is disappointing as the Mātanga group understand very well how the Blueprint could be operationalised in a range of responsive ways depending upon the school and community’s context. Realising the Minister of Education’s vision for an efficient and effective response was uppermost in our minds at all times. However, the Ministry of Education have now taken up the operationalisation phase and, at this point in time, their intentions are unclear. Despite this, the Mātanga conversations have continued and their feelings of responsibility to this work have increased.

Where to from here?

In New Zealand’s formal education system, principles derived from colonial images have continued to guide educators’ actions and explain the basis for those actions. From this pattern of images, discourses and principles, education policies and rules of practice are developed that require indigenous students to metaphorically, leave their culture at the school gate in order to participate in education (Bishop & Berryman, 2006). Indigenous languages, values, beliefs and practices have not been represented and legitimated within New Zealand’s classrooms and schools. The education provided by the state has played a major role in destroying Māori language and culture and replacing them with that of the colonisers.

In terms of schooling Whetu Cormick outlined some tangible and measurable goals that he wanted Te Hurihanganui to achieve, suggesting that he would only be satisfied when:

- All Tamariki Māori reaching year 13 report they had experienced no overt or covert racism at school.

- the educational success rates of all Māori are equal to that of Pākehā.

- the Māori perspective of our colonial history is taught to all school students in every school.

- every single school in New Zealand adopts a culture that is bicultural and bi-lingual.

- every aspect of the schools’ curricula includes Māori values, knowledge, tikanga, and measures of success that reflect what Māori understand as success.

Wally Penetito understood that both the problems and the answers were within our grasp. He understood that a better understanding of Te Tiriti o Waitangi could potentially help respond to the structural impediments through schooling as well as challenge all New Zealanders to open their hearts and minds to new possibilities:

Education is our business but it is not the answer to all our schooling problems. There are structural impediments that must be addressed before educational processes can be brought into play; and ensuring Te Tiriti o Waitangi in both its historical context and platform for future developments helps to establish a future Aotearoa New Zealand society that opens hearts and minds for all its citizens without prejudice.

Therese Ford works to create safe spaces for these critical conversations to take place:

Decolonisation involves firstly understanding how colonisation played out in our nation’s history and how it shaped and maintains our present institutionalised patterns of thinking and practice. It requires the psyche of educators at all levels of the system to be exposed and courageously critiqued so that internalised prejudice, derived from colonisation (either conscious or unconscious) can be challenged and de-centred.

Hurae White speaks for all the Mātanga when he calls for an immediate start:

It is time to change the negative assimilatory trajectory, address the disparities and call out the racist/linguistic undercurrents that exist in all levels of the sector.

Disrupting the hegemonic power of this way of thinking, requires a critical unpicking of the colonisers’ worldview and ways of being. This means understanding what is at the very heart of racism. Daniel Murfitt is clear that this is why the system itself needs to be addressed.

Te Hurihanganui came about because of the need to reclaim the space for Māori students and whānau within our whole education system.

Challenging the status quo requires the implementation processes to be different because the system is broken, the system is the tool that created the problem.

Conclusion

The concluding words come from Mere Berryman of Ngāi Tūhoe, Ngāti Awa and Ngāti Whare iwi, and are taken from those she prepared for the Te Hurihanganui launch at Porirua. This important event was held at Te Puna Mātauranga, an iwi-based centre that provides Māori learners and whānau with support to access and navigate the current education system.

Based on evidence and our experiences of what works for Māori in education, we believe the six interdependent design principles of Te Hurihanganui offer potential for developing an equitable and excellent education system where Māori students can be valued and belong and where communities are also contributing to and active participants in this change.

As we have seen too often in the past, the risk is that the six principles will be handed over to others to become a tick-box checklist, superficially understood and tokenistic; or even worse reinterpreted by those with the power to do so.

We, the Mātanga, stand behind our work and are determined to support this process going forward.

We know that this work is urgent. Another generation of Māori will miss out if we do not get this right.

These are worthy goals that few would disagree with and not want to aspire to. However, we know that a depth of knowledge of the evidence and lived experience of what actually works is crucial to take this work forward. Implementing Te Hurihanganui will not be effective if it is simply left to others to interpret nor will it happen if Early Childhood, schools and their leaders are left out of the conversation. We must all be up for both the culture change and the systems shifts that are required.

Our investment in education is the third biggest expense of Government. It is an investment in our collective potential, in all our futures. By 2021 the annual Government investment in the Education system is forecast to be $14.4 billion

The welcome investment in Te Hurihanganui is small in comparison to our overall investment in a system that is not delivering for all our children.

If Te Hurihanganui is to effectively address entrenched issues of inequity all the instruments of the system will have to play their part. This is not a Māori problem for Māori to fix up, this problem belongs to all New Zealanders.

References

Alton-Lee, A. (2015). Ka Hikitia Demonstration Report: Effectiveness of Te Kotahitanga Phase 5 2010-12. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Berryman, M., Eley, E., Ford, T., & Egan, M. (2016). Leadership: Going Beyond personal will and professional skills to give life to Ka Hikitia. Journal of Educational leadership, policy and practice, 30(2), 56-68.

Berryman, M., & Macfarlane, S. (2017). Hopes for the future: Indigenous knowledge as an enabler of potential. American Journal Of Indigenous Studies, 1(2), 19-127.

Bishop, R., & Berryman, M. (2006). Culture Speaks: Cultural Relationships and Classroom Learning. Wellington: Huia Publishers.

Bishop, R., Berryman, M., & Wearmouth, J. (2014). Te Kotahitanga: Towards effective education reform for indigenous and minoritised students. Wellington, New Zealand: New Zealand Council for Education Research.

Bishop, R., & Glynn, T. (1999). Culture counts: Changing power relations in education. Palmerston North, NZ: Dunmore Press.

DiAngelo, R. (2011). White fragility (2011) International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 3(3), 54-70.

Ermine, W. (2007). The ethical space of engagement. Indigenous Law Journal, 6(1), 193-203.

Ministry of Education. (2008). Ka Hikitia-Managing for success: The Māori education strategy 2008-2010. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education. (2013). Ka Hikitia – Accelerating Success 2013-2017. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o. (1986). Decolonising the Mind. The Politics of Language in African Literature. Nairobi: Heinemann.

NZSTA & Office of the Children’s Commissioner. (2018). Education matters to me: Key Insights. Wellington, New Zealand. http://www.occ.org.nz/publications/reports/education-matters-to-me-key-insights/

Office of the Auditor General (2012). Education for Māori: Context for our proposed audit work until 2017 Retrieved from https://oag.parliament.nz/2012/education-for-maori/docs/education-for-maori.pdf

Office of the Auditor-General. (2013). Education for Māori: Implementing Ka Hikitia – Managing for Success. Parliamentary paper. Wellington, New Zealand.

Shields, C. M., Bishop, R., & Mazawi, A. E. (2005). Pathologizing practices: The impact of deficit thinking on education. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Course Director Professor Mere Berryman says

the inclusion of a third wānanga in the programme recognises the value

participants placed on those mana whenua hosted events but it was also time to

revisit the course content.

Course Director Professor Mere Berryman says

the inclusion of a third wānanga in the programme recognises the value

participants placed on those mana whenua hosted events but it was also time to

revisit the course content.  "I think the blended e-learning is critical. We had some that were ready to grab it and run with it, and so by making those people kaiwhakaako who would take on a group of learners just helped that spreading across all our community. Effectively all of a sudden you’ve got a hundred people who are in ākonga groups meeting on a regular basis to talk about this stuff.

"I think the blended e-learning is critical. We had some that were ready to grab it and run with it, and so by making those people kaiwhakaako who would take on a group of learners just helped that spreading across all our community. Effectively all of a sudden you’ve got a hundred people who are in ākonga groups meeting on a regular basis to talk about this stuff.

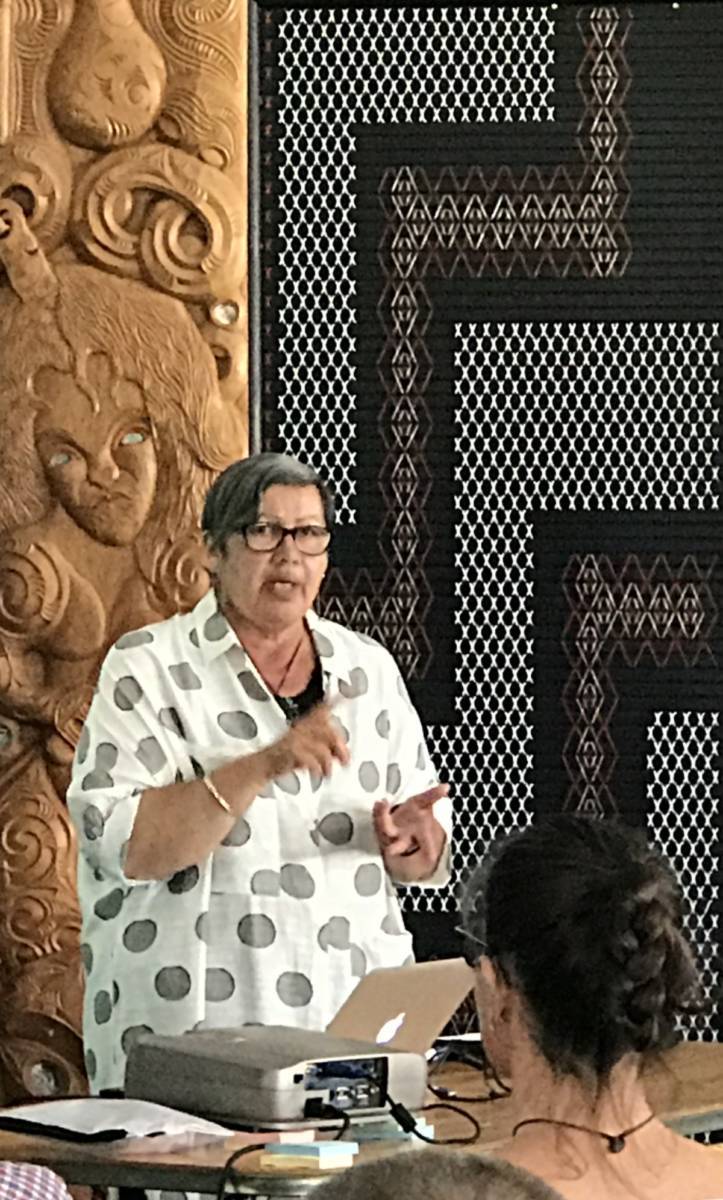

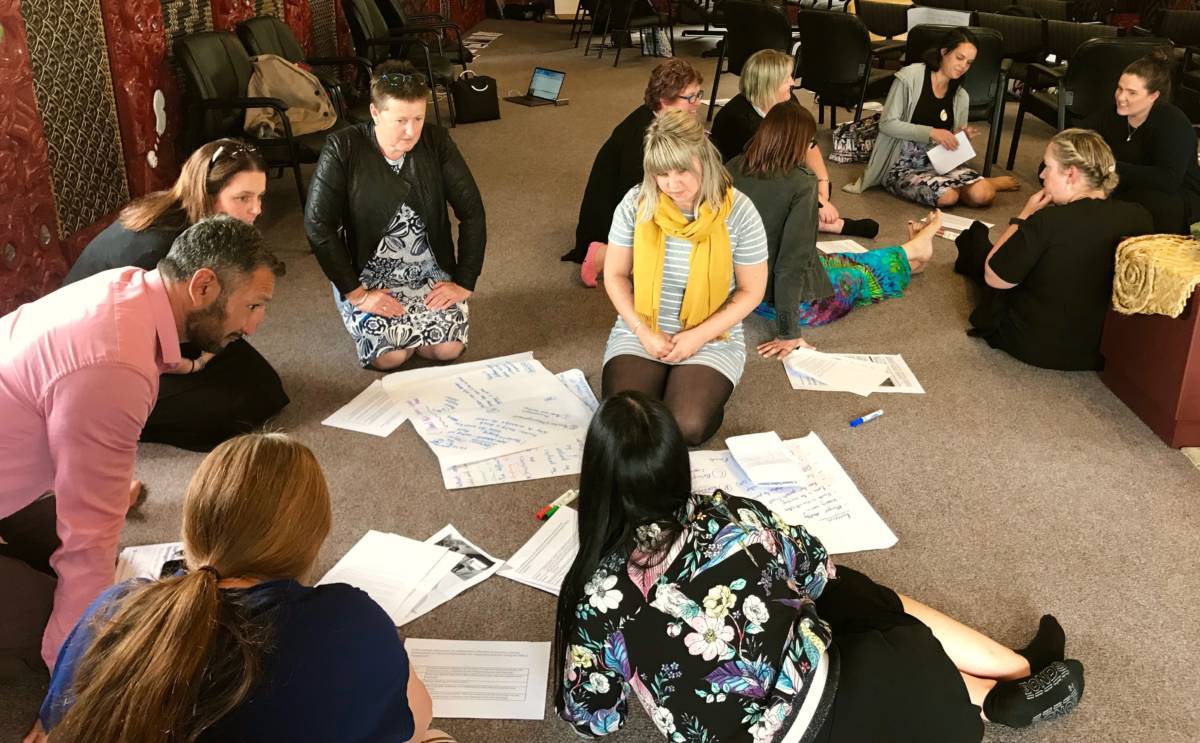

At the busiest time of the year, nearly 40 school and community leaders from throughout the North Island gathered to wānanga at Pukemokimoki Marae in Napier.

At the busiest time of the year, nearly 40 school and community leaders from throughout the North Island gathered to wānanga at Pukemokimoki Marae in Napier.

On the first day, Mere Berryman provided the group with critical perspectives with which to challenge the biases and prejudices that run through our society, schools and the sector generally.

On the first day, Mere Berryman provided the group with critical perspectives with which to challenge the biases and prejudices that run through our society, schools and the sector generally.

After dinner on the first night, Te Kura Reo Rua o Maraenui Tumuaki Chris Worsley helped facilitate a discussion about individual acts of leadership.

After dinner on the first night, Te Kura Reo Rua o Maraenui Tumuaki Chris Worsley helped facilitate a discussion about individual acts of leadership.

The individuals attending didn’t need convincing that widespread reform is required; their commitment to the kaupapa is visible in actions already taken.

The individuals attending didn’t need convincing that widespread reform is required; their commitment to the kaupapa is visible in actions already taken.

Despite repeated attempts to reverse this injustice, an inevitable and inter-generational decline in the wellbeing of Waitaha iwi began.

Despite repeated attempts to reverse this injustice, an inevitable and inter-generational decline in the wellbeing of Waitaha iwi began.

On Monday morning, Kaiwhakaako responsible for leading the Blended Learning within individual schools moved from meaning-making to collectively constructing next steps in activating transformative change.

On Monday morning, Kaiwhakaako responsible for leading the Blended Learning within individual schools moved from meaning-making to collectively constructing next steps in activating transformative change.

With former students joining their teina to tautoku them, the Year 12 and 13 students prepared and served all the meals over the two days.

With former students joining their teina to tautoku them, the Year 12 and 13 students prepared and served all the meals over the two days.