Marsden-funded research

Posted on 27 April, 2021

Languaculture is a term meaning that a language includes not only elements such as grammar and vocabulary, but also past knowledge, local and cultural information, habits and behaviours. The term was coined by the American anthropologist. Professor Emeritus Michael Agar.

The Poutama Pounamu team has received Marsden research funding to understand how languaculture plays out in the inter-relationships between language and culture as it relates to infants, their whānau (families) and home communities across three hapū (sub tribal) settings.

To do this, the team wants to learn more about conception, birth and infancy, from precolonial Māori ways of viewing the world.

To do this, the team wants to learn more about conception, birth and infancy, from precolonial Māori ways of viewing the world.

We also want to understand the experiences of whānau with babies learning to communicate into their home culture as the basis for being able to fully communicate in the more traditional schooling forms of communication that lead from speaking to reading and writing.

What do tamariki know?

From a precolonial Māori view of the child, we know that each child is unique and born of greatness. Within the word tamariki - that we all too often translate as ‘children’ - are two metaphors that speak of tamariki Māori as carriers of the divine spark from Tama-nui-te-rā (tama the sun) and created in the images of Ariki (the Gods) tama-ariki. (see footnote 1)

However, we also know that too many tamariki Māori are storied on entry to school as “knowing nothing”.

While we understand there might be tamaiti (metaphorically the ‘little sun’, translated as ‘child’) who do not know or are unable to do what the teacher wants them to know and do, we want to understand what actually may be in their cultural toolkit, their prior knowledge and experiences, that continues to be missed or belittled so that the divine spark with which they enter school soon begins to be dimmed or even extinguished.

Considering the impact of assimilation

For too many Māori children, the interrelationships and subtleties of language, culture and identity generated from Indigenous epistemologies have been eroded, belittled and overlooked by an education system and associated education policies that continue to promote assimilation into the worldview of the coloniser; a world view that is also grounded in racial hierarchies.

For too many Māori children, the interrelationships and subtleties of language, culture and identity generated from Indigenous epistemologies have been eroded, belittled and overlooked by an education system and associated education policies that continue to promote assimilation into the worldview of the coloniser; a world view that is also grounded in racial hierarchies.

In New Zealand, this situation has continued to detrimentally influence how Māori have viewed their own language, culture and identity across successive generations, and how it is viewed by others.

By better understanding the socialisation of our tamariki and mokopuna (metaphorically the spring of our gene pool, regularly understood as ‘grandchildren’) from conception, we want to support more effective social interactions through early childhood and schooling, so that improved communication and hauora (wellbeing) is able to flow across other home and school communities.

We understand the importance of clear communication to one’s sense of belonging, emerging identities and later language and literacy acquisition. However, we know that for too many Māori this strong sense of belonging and belief in one’s own agency and voice is not happening. Research shows that this is intergenerational, pervasive and harmful. (see footnote 2)

About the researchers and communities

The research team comprises two principal investigators (Dr Mere Berryman and Dr Lesley Rameka) and three associate investigators (Karaitiana Tamatea, Tracey Togo and Diana Cruise).

The research team comprises two principal investigators (Dr Mere Berryman and Dr Lesley Rameka) and three associate investigators (Karaitiana Tamatea, Tracey Togo and Diana Cruise).

These associate investigators are part of three different hapū communities either through whakapapa connections or at their invitation. All researchers are Māori.

Our main research question is:

How can a richer appreciation of traditional Māori-related knowledge, together with infants’ languaculture as relational dialogue, help to revise our understandings of hauora and legitimate literacy learning for infants?

Our research methodology

Participants are being selected from three different marae communities in different regions of the North Island (Tauranga, Waikato and Wairarapa). In each marae community we are working with up to six separate whānau groups, each with at least one infant (including some who are yet to be born) and up to 10-15 whānau members.

Participants are being selected from three different marae communities in different regions of the North Island (Tauranga, Waikato and Wairarapa). In each marae community we are working with up to six separate whānau groups, each with at least one infant (including some who are yet to be born) and up to 10-15 whānau members.

In each of the three marae settings, potential participants are identified using cultural encounters and procedures such as whanaungatanga (kinship ties through family connections or other networking).

Currently we are working with identified kaumātua (elders, both male and female) and other interested whānau members in the first marae setting.

We have explained the research and those who wish to participate are working with us to begin to share their traditional and contemporary stories and their current knowledge and experiences.

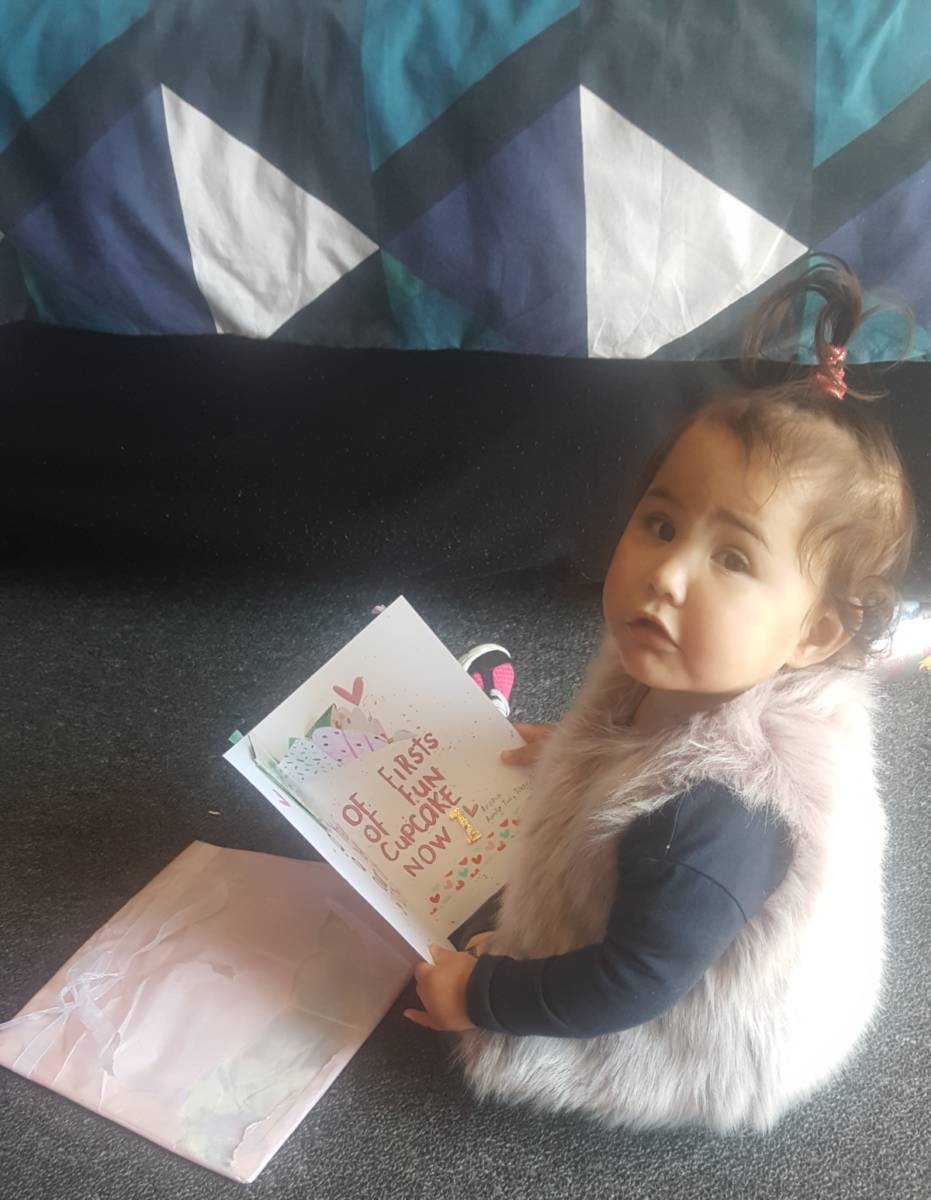

Whānau with babies have been invited to talk with us and to take cellphone videos of infant dialogue including writing down and/or recording what they understand of its significance. They will then post their video and understandings onto a private shared-group Messenger chat page for collective viewing and researcher analysis.

Kaumātua and whānau stories have been transcribed, checked, annotated and agreed upon through a dialogic process and as part of collective and culturally appropriate protocols and processes. This means that the metaphors and theorising constructed by these participants were most often from their own whānau and hapū cultural context.

Emerging themes

Three main themes have begun to emerge from the Tauranga Moana whānau that are represented in both the narratives of kaumātua and parents. These include:

Three main themes have begun to emerge from the Tauranga Moana whānau that are represented in both the narratives of kaumātua and parents. These include:

- Te Whare tangata - (the house of humanity also translated as the womb or

uterus) - nurturing of the mother will in turn increase our ability to nurture the child and therefore our next generation. - Rūaumoko – (the deity of earthquakes and volcanoes metaphorically the

rumbling of Rūaumoko signifies a new descendant) - the unborn child and their connection to their cultural identity is essential. This includes who they are, who and what they might become, and how this might occur.

- Tamariki – hauora of our tamariki and their mothers begin by better understanding and using traditional Māori practices from birth.

Of particular interest from this initial engagement are the links they made to the importance of the holistic wellbeing of the child and essential to that was the importance of the revitalisation of cultural knowledge and practices.

If it takes a village to raise a child, this hapū, the immediate families of these babies and their wider hapū community are all wanting to take joint responsibility. However, the challenge will be - what about those parents, babies and tamariki who are no longer closely aligned to their whānau and wider whānau through their marae communities? How can we contribute then?

Footnotes

1. Eley, E. M. A. (2020). Fanning the divine spark: Gaining understandings of micro-interactions in New Zealand classrooms

2. Ngaamo, R. B. (2019. Through the eyes of whānau: Destruction of cultural identity through education