5

Chapter 7 of the School Leadership BES (Robinson, Hohepa & Lloyd, 2009) is entitled Creating Educationally Powerful Connections with Families, Whānau, and Communities (p.142). Within this chapter, Alton-Lee, Robinson, Hohepa and Lloyd draw from extensive research to provide three reasons which describe why school leaders should concentrate on developing partnerships and connections with family, whānau and communities. These reasons are detailed below:

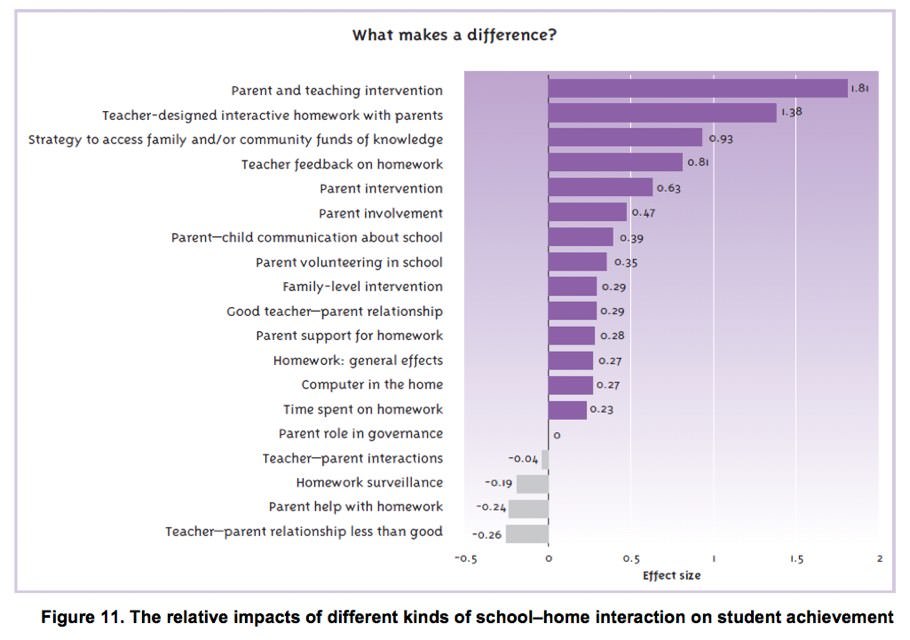

- Connections with family, whānau and communities have the potential to enhance outcomes for all students, especially those who have been under-served or are at risk. Certain kinds of school-family connections and interventions can have large positive effects on the academic and social outcomes of students.

- However, some kinds of engagement with families and communities can be counterproductive. It is important that school leaders promote engagement that is effective.

- By establishing educationally powerful connections, leaders gain access to a greater range and depth of resources to support the work of their schools.

Some of the research reported on in this chapter reflects the work of Dr Mere Berryman and in particular the findings from her research with Māori whānau and communities. Dr Berryman discusses some of these findings in the following video clip.