Key thought

“Putting them in a strong position to learn positively.”

Key questions

- How do the practices of the leaders, teachers, tutors and parents in this video clip support students to be in a strong position to learn positively?

- What implications, opportunities and questions does this video clip highlight for your school?

Hearing sounds in words is part of reading

While hearing the sounds that letters stand for, and knowing the names of letters, can help students who are learning to read, there is a more to reading than this. Most adults have ideas about how they learned to read.

For example:

"My goodness, we had to know our sounds in those days!"

But reading is far more than syllabification or sounding words out.

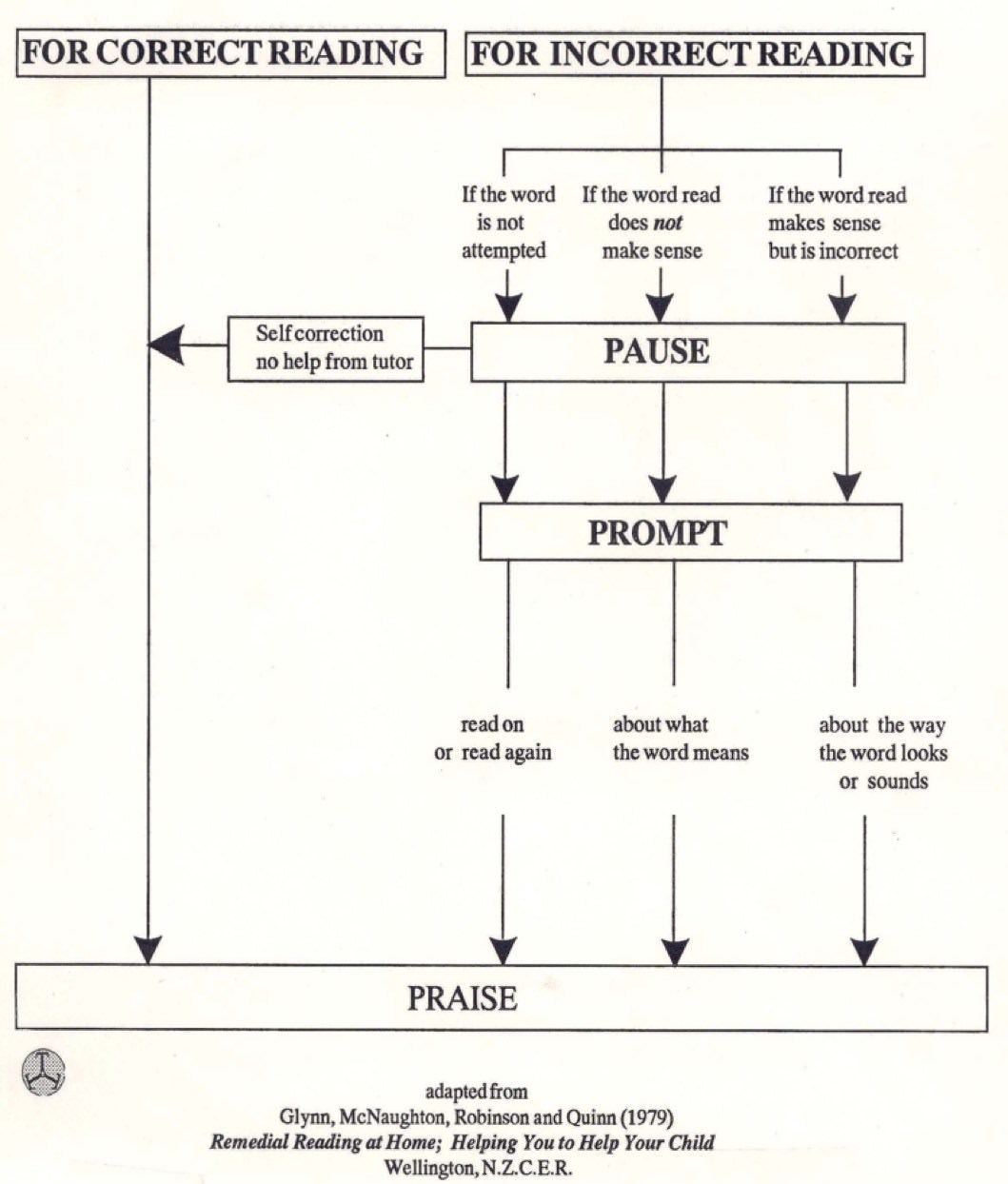

The poem on the following page (Resource 2) provides tutors with an opportunity to discuss what range of reading prompts are necessary, and why reading is more than just sounding words out.

14

I take it you already know of tough and bough and cough and dough?

Others may stumble, but not you

On hiccough, though, slough and through?

Well done! And now you wish, perhaps,

To learn of less familiar traps?

Beware of heard, a dreadful word

That looks like beard and sounds like bird,

And dead: it’s said like bed, not bead -

For goodness sake, don’t call it deed!

Watch out for meat and great and threat,

(They rhyme with suite and straight and debt.)

A moth is not a moth in mother

Nor both in bother, broth in brother.

And here is not a match for there,

And dear and fear for bear and pear,

And then there’s dose and rose and lose -

Just look them up - and goose and choose,

And cork and work and card and ward,

And font and front and word and sword,

And do and go, and thwart and cart -

Come, come I’ve hardly made a start!

A dreadful language? Why, man alive!

I’d learned to talk it when I was five,

And yet to write it, the more I tried,

I hadn’t learned it at fifty-five. - Anon.

Key questions

- What does this poem exemplify or tell you about the English language?

- What cognitive strategies did you draw on to read this poem?

- What are the implications for readers who depend on sounding out letters?

- What are the implications for readers who have learned to read in another language first, for example te reo Māori?

Some basic ideas about students reading

Opportunities to read orally in a one-to-one situation provide an important assessment context.

- Students learn to read by reading.

- Praise and support will encourage their attempts to read successfully.

- Students reading and their attitudes towards reading will improve when:

- they are working with someone who gives them encouragement and appropriate help;

- they are provided with interesting material which is at their instructional or independent level;

- their behaviour leading to independent reading is encouraged and praised.

15

Selecting a suitable book

Successful use of Pause Prompt Praise depends on readers having access to a variety of text material that is:

- of interest to the reader, and

- of appropriate difficulty.

If a text is too difficult or challenging for the reader they are likely to make too many errors. This can result in the text losing meaning and the reader becoming disheartened and frustrated.

Conversely, if a text is too easy and too few errors are made, there will not be sufficient opportunities for the tutor to utilise the Pause Prompt Praise strategies and for the reader to learn to practise the skills needed to correct their errors when they are reading alone.

Successful use of Pause Prompt Praise, therefore, requires regular monitoring of the readers accuracy levels so that the levels of the text can be adjusted (upwards or downwards) to maintain an optimal difficulty level of challenge for the reader and tutor to work together.

This is often referred to as the zone of proximal development (Vygotsky, 1978).

A useful guide to selecting texts that are the appropriate level of difficulty is to count off 50 words from a selected book or story.

If the reader makes five or more errors within those 50 words then the text is too difficult and another text will need to be selected.

However, if the reader makes two or less errors, it is too easy to use in Pause Prompt Praise tutoring sessions as there will be insufficient challenge for the reader to develop their reading strategies. Ideally text should:

- be of interest to the reader

- be within their range of experiences

- be what they can talk about

- provide about three to five opportunities in every 50 words to practice their self correcting skills.

16